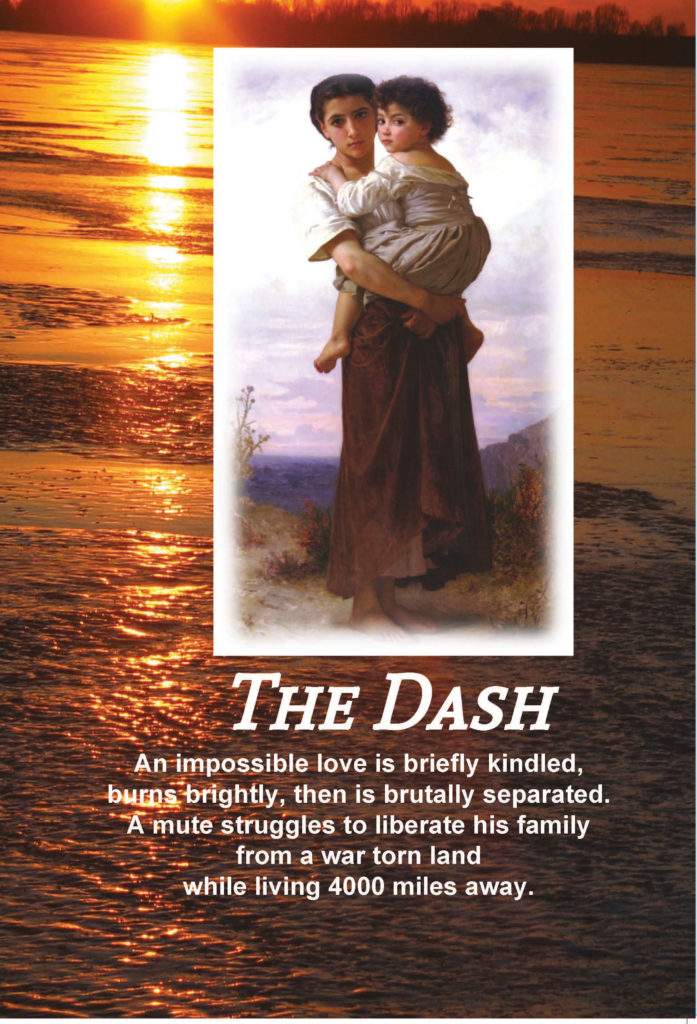

Sample Chapter

Chapter 1

The Dance

Litomysl, Czechoslovakia, Sat April 15, 1916

Why does a headstone cause us to reflect? About dates that state, the birthing and the dying? Was that all there was to tell? Or is it? The dash between?

|

From the ashes of rotting oak leaves, sprang forth with the sweet smell of lilac splashed spring. The first wedding dance of the season was always a big affair, and tonight was no exception.

In the waning daylight, not quite dark nor full light, a tall figure shuffled along. Flashes of lightning, from the last rolling thunderstorm, revealed a tall man, carrying a large black case. A tattered black hat, wet with rain and sweat, drooped over his uncut blond hair. He was soaked to his skin; his coarse, hand-spun shirt outlined his tight muscular body.

He walked with stiff, awkward movements, stumbling and mumbling to himself, “No want do.––Papa say do, so I do.––No place at home––make own way.––Mama want stay.––Papa say go––find what to do. People––laugh––call me dumb––I stay home, but papa say––go––try.”

The Tanecní dum (dance house), was an unpainted building, the site of weddings and celebrations for the last fifty years. Strung around the outside, wrap-around porch were bright kerosene lanterns swinging from dainty silver chains. The lanterns flashed and, danced with the shadows on the walls. This porch, was where young lovers, of all ages, strolled hand in hand, sometimes closer; hoping for a lantern to run out of fuel, so to snitch a kiss in the darkness or sooner.

From the door of the dance house, the lively music of a Roma band drifted out across the wet grass. The fresh night air painted an extra touch of melancholy on the music. A rain-soaked haze hovered over the newborn grass; tulips and daffodils tentatively peeked at the evening sky.

A group of young men, belonging to the Freikorps gang*, stood in a circle on the dance house steps, smoking cigarillos and passing a bottle of brandy around.

With faltering steps, the tall man tried to climb the steps, tripped and fell to his knees. One suspender of his overalls slipped off his shoulder, down to his waist. He struggled to get up, rolled on his back, still gripping to his black case. Trying to rise, a foot pressed down on his shoulder.

From the top step, Ales Baum, the leader of the gang, spat and sneered down at the man. “What’s a matter, clumsy fool, too much Slivovice (plum brandy)?” He bent over the wet man and blew a circle of smoke in his face.

“Ah––ah––no––steps––slip––slippy.” The man fervently peeked up at the gang out of the corner of his eye and tried to rise again.

The rest of his group crowded in. The odor of brandy, beer and cigars all rolled up in a blanket of week-old sweat, emanated from them. One member gave the man a nudge with his foot. “Let us peek in your case.”

The man held on with both hands and pulled his case closer as he stood up. “Ahh––ah––is––tuba.”

Ales snorted. “Ha! Listen guys, listen to the dummy! Tuba? Hell, only a big man can play the tuba! A smart man! That ain’t you. I think we will try it.”

Ales raised a small swagger stick and rapped the confused man on his knuckles. The man howled in pain, stepped back and dropped his tuba case. Ales grabbed the handle of the case and jerked it away. The man mouthed words, but no sound came out. He tried again to retrieve his case, but each time he reached out for it, the Freikorps passed it off to another gang member. Hooting and laughing, they prodded the man, again and again, savoring the enjoyment of their perverse pleasure.

*Freikorps (Free Corps) German voluntary armies formed in German lands

The man moaned, “Ooo––No take––no take!” He wrung his hands together, rocked back and forth examined his shoes.

“This is no fun! We need more brandy,” Ales said. “Let’s go, men! Here’s your damn piece of junk!” He threw the case at the man’s feet. Sheets of music and a badly dented Helicon tuba rolled out on the ground.

|

Ales snarled. “Those are stinking gypsies in there, they won’t let you play with them; you’re a Czech and a damn poor one. They won’t mix with a tongue tangled fool.” The strutting gang slapped each other on the back, congratulated each other for another victory won and swaggered into the dance.

The man picked up his papers and horn, placed them back in his case, climbed the steps and peeked in the door. Then he slipped into the dance house, pasted himself against the wall, fidgeted from foot to foot, clutching his case to his chest.

Building his courage up, the man carefully, step by faltering step, resumed his journey into the dance house. An odorous wave of stale beer, week-old cigarette smoke, and unwashed sweat floated on the humid air. It hit him in the face, as the room exploded with music. The bewildered man shuddered, peered around the hall, and blinked his eyes adjusting to the bright light.

Inside the large octagon room, lanterns hung in a crazy quilt order, splashing puddles of light on the well-worn dance floor. Warped floorboards, thanks to a leaky roof, curled and marred the floor. Rather than fix the floor or the roof, the frugal dance house owner gave the warped floor a liberal dose of powdered dance floor wax. The boisterous dancers paid no heed to the occasional stumble. They were having too much fun dancing, drinking, and whooping it up.

The confused man edged his way up to the ticket counter at the entrance to the dance floor. “In––please,” he mumbled.

A short, thin woman, a cigarette dangling between her left-over, two front teeth, gave the man a quick smirk. “Hello handsome,” she cackled and blew smoke. “Tickets are two korunas (Czech Money) for beer, three korunas for the dance and a little fun later costs ten korunas.”

The woman rubbed her hand up his arm, twirled her bleached blonde hair with her other hand, showed her best ten-koruna grin and winked at him. “What’ll it be? Get out of those wet clothes? I’ll treat you to a good time!”

“Aoo––I––need––look––band––how much––that?

“We don’t have any looking price! Give me five korunas; I’ll give you a ticket and a beer! And a discount for later. What d’ya say?” Her sagging face lit up in a nauseous suggestion of temptation, almost erasing her deep wrinkles.

“Aah––five koruna––me do.” The man laid his money on the counter.

“Good, don’t forget about later, you won’t regret it!

The man weaved through rows of randomly placed, mismatched tables and chairs. He made his way to one side of the band and sat down at a deserted corner table next to the men’s bathroom. Wrinkling his nose at the odor emanating from the bathroom, he swatted the flies away and set his black case on the table. What I do here? ––I farm not play tuba. ––Papa say, “Zuba, go to the dance house, get a job. Make money. ––Play the tuba in the barn for cows don’t put no koruna in your pocket; it just irritates the pigeons.”

Up on the bandstand, a Roma family band played. A young girl stepped down from the bandstand slapping a tambourine in her hand and beating out a staccato rhythm. Her green satin blouse shimmered as she swayed to the music; her long black hair floated around her shoulders in ringlets. Her pale skin shone from her perspiring efforts, as her fiery dark eyes cast out, ‘come-hither, maybe later,’ glances.

Peeking, above the case, Zuba closely watched the whirling Roma girl. Whenever she came near him, she flashed a pretend smile and coyly waved to him. He wasted his return glance by quickly lowered his head behind the case. When she turned away, he raised his head and eyed her. Maybe I find a girl like her––I don’t talk no good. She’s Roma. ––Not allow me to see her. No girl want me. All girls in Litomysl laugh at me. What I do here?

Zuba’s eyes followed her every move. The curve of her body, the gold hoop earrings, and her uncharacteristic, pale skin. Her sensual nature cast a spell of desire over him.

When she came near, his eyes quickly counted the squares of the checkered tablecloth. A whiff of her lavender splash water engulfed him, signaling her nearness. It snared him, his heart beat faster, his breath caught in his chest and he trembled. If only, ––but Papa said: “Zuba, stay with a simple woman that cooks good, the wedding night lasts just two, three days, cooking stays longer.”

On the dimly lit bandstand, sat Bolda Danka, the father, a broad, muscular man, with dark curly hair. He covered his head with a bright red headpiece. He nodded in time to the music as he strummed a gayly painted guitar.

|

Florica Danka, the mother, wore a yellow headscarf, a colorfully embroidered vest, and her salt and pepper, dark hair pulled back into a bun. She sat behind her Cimbalom, her playing sticks racing over the instrument

Their daughter, the one who danced past Zuba, is Eliska Danka. She wore a colorful purple scarf wrapped around her raven black hair, large gold hoop earrings, and a gay yellow hip scarf around her waist. She sang, played the fiddle and pounded a mean tambourine. She is front and center, constantly in motion; with a swagger and a wink, she kept the party going. When not performing, she timidly retreated to sit quietly behind her mother.

Eliska’s short, younger brother, Hanzi Danka, squeezed out tunes on his scratchy, squealing accordion. He wore a red and gold, embroidered vest, a colorful blue satin shirt with billowed bishop sleeves and wrapped his head with an orange scarf. He always smiled and winked at any girl that caught his eye.

Two curly headed, one-year-old twin boys, Luca and Stevo, crawled on the floor, around Florica’s feet. The instruments they played were wooden toys made by Bolda.

Jacob Conkova, the only none family member, covered his balding pate with a white scarf and wore the plain clothes of a farmer. He played clarinet with a sour disposition. Between songs complains that his pay isn’t enough for his skill level.

The inebriated dance house owner staggered up to the bandstand. “Hey, gypsy! Play the Czech music with the tuba beat!”

Bolda shrugged his broad shoulders, “We can’t! Got no tuba!”

The owner blew a puff of smoke and pointed his cigar at Bolda. “Well, you damn well better get one, or pack up and get out of here. Who da hell do you think you are? I hired you; you play a good old polka!”

Bolda glared at the owner, “Maybe, you pay us, and we leave.”

The owner wiped his hands and sweaty forehead with a dirty towel and slung the towel over his shoulder. “Pay you? Like hell, I will! Get a tuba or get your gypsy asses out of here! You have ten minutes!”

Bolda stood up, doubling his fists. Florica reached over and grabbed her husband’s sleeve and pulled him back to his chair.

“Now, now Papa, please be patient, we need the money,” Florica cried.

“I know. We played all night already, damn Gadjo*, trying to cheat us.”

Eliska interrupted, “When I was out dancing, a big Gadjo is sitting in the corner. He might have a tuba. Seems slow, though.”

Bolda placed his guitar down and stood up to see the man better. “He’s not Roma. We don’t mix with his kind. Bad enough, to play for these Gadje*, we can’t let them in the band. Probably can’t play a lick. He has no Romanipen* and looks like the mule’s rear end.”

“Just this time,” Hanzi said. “We need the money awful bad, awful bad. Eliska ask him! Please, Papa, she can do it, watch and see.”

*Gadjo Anyone who was not Roma. *Gadje non-Roma plural

*Romanipen – Roma adopted the Romanipen code to survive in certain circumstances, such as the persecution they suffer and assimilating into a foreign society. Following this code helps the Roma preserve their ethnic identities and values in each of the countries where Roma live.

Eliska retreated behind Florica. “No Papa, please! I’m afraid to talk to him. He peeks at me, that’s bad enough. When I look at him, he puts his head down kinda sneaky like. I can guess what he’s thinking. Gadjos can’t be trusted; they are only interested in one thing.”

“Don’t be afraid Eliska, we will be close by, I protect you,” Hanzi cajoled.

“No!” Bolda replied, “It is not proper. I promised Eliska to Jacob!”

“Oh Papa, ask him if he plays, just this once,” Florica interjected.

Bolda rubbed his chin whiskers, “All right, but Hanzi you do it. If it doesn’t work, I can kick him out, and Hanzi, get to the point, don’t be jabbering so.”

Hanzi twirled his little black mustache between his fingers, adjusted his vest and ran across the dance floor. Coins, dangling from his belt tinkled out a rhythm, on the way to the table. “You got a name, big man?”

“Ah––Zuba,”

“What do you have in your case?”

“Tu––ba.”

“Zuba! Zuba with a tuba it works, it works,” Hanzi tweaked his mustache again. “Are you hiding a horse or your lunch in there too?”

Zuba slowly raised his head from behind the case, but wouldn’t look Hanzi in the eye. His mouth shaped words, and finally stammered out a weak moan, “No––No––horse.”

“Well, you are something else,” Hanzi said. “Why do you have your black hat pulled down over your ears? Your ears cold? Bet you have big ears! Big ears! Stick right up through the hat, I bet. You know what? I’ll just cut holes so they can stick out. Some holes, so the ears stick out, that’s what I’ll do.” Hanzi drew a small silver dagger from his vest. “It’s just the thing to do. See this?”

Zuba’s words tumbled around in his mouth. Sweat beaded on his upper lip and dripped on the table. “Ah. ––No––doon do––dat!”

Hanzi raised the silver dagger. His teasing tone now turned to a hard edge “I’ll cut you some holes. Let the ears stick out. You will look like a donkey pulling a hay rack! A hay rack, I tell you! Just a big old donkey! Can you hee-haw like a donkey? I hear nothing else out of you.”

Hanzi reached for Zuba’s hat, but before he laid a finger on the hat, Zuba wrapped each of Hanzi’s childlike hands in each of his big hands. “No- do,” Zuba said. “No––hurt––hat.”

“Let me go, you… you… before I kick the devil out of you!” Hanzi screamed and kicked at Zuba.

Zuba stood up. Squeezing Hanzi’s hands in an iron grip, Zuba raised his arms toward the ceiling. Painful concern crept across Hanzi’s face as his feet left the floor, and his dagger clattered away.

“No––do––dat,” Zuba said. “I––no––want––hurt––you.”

“Let me down, you, you, … I’ll stomp the devil out of you I say! You will wish you were a donkey when I get through with you, put me down and you’ll see,” Hanzi stammered, as his eyes flitted from Zuba’s face to the bandstand. Where is papa? Help me.”

Zuba shook him. “Make––no––trouble?”

“Put me down and or I’ll throw you against the wall. That wall over there. Right through and I’ll mop this place up with you, bust you up, stomp you into the mud,” Hanzi wailed.

Zuba stood perplexed, not knowing what to do next.

Hanzi blubbered, “You better be careful; I’m small but tougher than old horse leather, rougher than old horse leather I say! I don’t take no sass from a Gadjo,” By this time Hanzi’s eyes watered, and he blinked a punctuation mark with every word he said. “Papa, please come! Help me!”

“You––no––gonna––do––dat -no more?”

“Let me go before I really get mad; I can get sore, you know. There will be hell to pay, I tell you! I just wanted to see if you are a tuba player. And you jump me!” The pain in Hanzi’s hands went from ‘damn that hurts’ to ‘passing out’ pain. “Papaaa!”

At the mention of the tuba, Zuba’s face lit up with a ‘Christmas morning’ grin. He relaxed his grip, and Hanzi fell to the floor.

“I––play––tuu––ba––good,” Zuba said.

Bolda heard Hanzi’s call for help. He ran over and sized the large man up, “I might teach you a lesson!” He hesitated, picked Hanzi up, and brushed off the dance floor wax from Hanzi’s back. “Are you all right?”

“I’m all right! Don’t fight him, Papa,” Hanzi said, trembling and rubbing his bruised hands. “I scared him so he put me down, I was teasing him, and I guess he can’t take it.”

Bolda shook Hanzi by the shoulders, “Did you do anything to start this?”

Hanzi squirmed and dodged the question. “Papa, you know what? I found out he don’t have no horse in the case; he has a tuba! Just what we need! And in a place like this Papa, not his lunch Papa! A tuba! He said he plays it too! So, he says. Maybe just blowing steam. Should we try him, Papa? If he can’t play it, at least I tried. Right, Papa?”

Bolda eyed Zuba warily, but stayed out of the reach of the big man’s long arms. “I don’t know; seems daft in the head. Play the tuba? Don’t think so. That takes a man with thinking skills. Do you play by ear? We play by ear, no music on paper.”

Hanzi peered around from behind Bolda and giggled. “With those ears, he should do a bang-up job, simply great. Play on either side, I bet. Hee-Haw, Hee-Haw, you play by ear, big guy? Huh, no way,” Hanzi said.

“I––play––tuu––ba––gud,” Zuba said, a note of calmness and pride crept into his voice.

Bolda slyly glanced at Zuba and stated “Well, I tell you what, we need a tuba player in the band. You must try out, of course. I need to hear you play. What you say?”

“I––play––tuu––ba––gud––I––show. ––I––come tomorrow and––play for you.” Zuba pulled his hat down on his head, his trembling hand grasped his tuba case, and he turned to leave. Need to––get out of here. Go back to farm. I showed my Papa. I come here. ––Leave before I wet my pants.

Hanzi spit on the floor. “Tomorrow? Wait until tomorrow? I told you he was blowing steam. Bet he never comes around again,”

Zuba stopped, turned back bewildered, “No––I––come.”

Bolda winked at Hanzi and said to Zuba, “Well, we’ll do it, right now. Just a tryout, no pay mind you,”

Zuba glanced at the dance floor.A crowd had gathered and stared at him.The bucket of courage he had filled up, walking the seven miles to the dance house, now quickly leaked dry. “Oo––I––doon––know––lots––of––people––see––me––I––doon––know––Oo––no.”

“Don’t worry, we’ll put you in the back, all anyone will see is your tuba. You can hide back there,” Bolda said, waving at the bandstand.

“Ya, way back, out in the yard or by the lake! Is that far enough away?” Hanzi chuckled and sneered to no one in particular, “I told you he is a big bag of air. He can’t play the tuba a lick.” Zuba cashed in the last scraps of courage, and replied, “I––play––tuu––ba––gud––I––show,” Zuba nodded at Bolda. “I––show––right––now.”

“Go to the bandstand. I’ve got business to attend to. I’ll be right back,” Bolda said, relieved that things might work out.

Bolda found the dance house owner, leaning against the wall, leering at a barmaid and rubbing her back. She reluctantly pretended to accept the unwanted attention as she calmly smoked a cigarette.

“We have a Czech tuba player; can we get paid please?” Bolda said firmly, trying to show the owner that he was in charge.

The owner didn’t look up, but kept rubbing the barmaid’s back. “What tuba player?”

“Right up there! He’s taking the tuba out of the case?” Bolda said.

“OK, I’ll pay you after the polka,” said the owner, still nibbling on the barmaids left ear.

“All right, you better,” Bolda said.

Bolda walked back across the floor, climbed the bandstand and sat next to his wife, Florica.

“Did you get a tuba player? Is the owner going to pay us now?” A worried Florica asked.

“Yes, we get paid after the polka,” Bolda said, through his clenched teeth.

“The tuba player, is he any good? A little slow, I think we should forget about him,” Eliska said retreating further behind her mother.

Bolda picked up his guitar. “He’ll be all right; we’ll just keep the big ox around long enough to get paid,”

“All right, big fellow, can you play the Praha Polka?” Bolda said.

“Ya––Farewell to Prague––sure. I––need––valve––oil first.” Zuba reached behind his chair to get the valve oil from his instrument case. When he did this, Jacob Conkova slipped up and stuffed a large rag into his tuba. Zuba oiled the horn, making sure the valves slid up and down to perfection. “OK––I––ready!”

The band launched onto the music, and Zuba played. The usual sound of the booming tuba sounded like a constipated cow. Zuba hesitated, took his lips from the mouthpiece and said, “No––sound.” A frustrated Zuba examined his tuba thoroughly.

Jacob guffawed, slapping his knee, “See the big ox, he can’t make a noise with his mouth or tuba!”

“Jacob, please don’t, we will lose the money. He might be all right.” Eliska said quietly.

“I want to have a little fun with this Gadjo, what’s a matter with that? You soft on this man-child? Mind your own business, woman,” Jacob muttered. His eyes burned a contemptuous stare at her. “We aren’t married yet.”

“I’m sorry to upset you, but if he can’t play, we don’t get paid. How is that any good?”

“We don’t need him.”

“We need him, shut up Jacob!” Bolda hissed under his breath.

Bolda stepped up and pulled the rag from Zuba’s horn and threw it at Jacob. “Here’s your trouble. Trouble begets trouble, doesn’t it, Jacob?”

Zuba’s face blossomed a bright red, his mouth moved, but not a word escaped. I so dumb, ––in front of the beautiful lady––What I do here? ––I should be in the goat barn that’s where I belong, in the goat barn. ––Who do I think I am? A great tuba player? ––Will my horn talk for me? ––With a rag in it? Didn’t even see it. ––I’m dumb enough to jump high in a room with a low ceiling.

Eliska, sensing Zuba’s turmoil, spoke up, “It will be all right. Never mind Jacob, he means well, but sometimes doesn’t think too far ahead. Just play your horn; you will do fine.”

Zuba’s face beamed, a warm rush came over him. She said I do okay.

“Are you ready to play Zuba?” Bolda asked, casting a hard glance at Jacob.

Zuba’s mouth froze in a silly grin, he nodded and lowered his eyes. He raised his tuba mouthpiece to his lips and played. “Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump Bom bump.”

The band joined in, and the Praha Polka was on its way. When the song finished, all were pleased that the polka had gone well, but no one said a word to Zuba. All except Eliska, she nodded and gave him, “thumbs up.”

Upon seeing this, Jacob burned with rage and jealousy. He threw his clarinet in the case and spit on the floor.

Bolda left the bandstand to find the dance house owner and collect his money. After finding him, he came back with a handful of cash yielding five hundred korunas.

“That’s it for tonight, let’s go home,” he said to the band, and then he paid Jacob fifty korunas.

Jacob said, “I bet you will pay me more when I am your son-in-law, eh?

“I paid you fair. We agreed.” Bolda said.

“I carry the band; I should get more,” Jacob replied.

“We could play without you next time, and you get nothing, that’s fair too,” Bolda snapped.

Zuba was putting his tuba away when Eliska timidly approached him. “Thank you. You play well.”

A red flush crept up Zuba’s face, slipping under his blond hair; his breath came gasps as he tried to speak, but a nod was his only reply.

Jacob pushed himself between Zuba and Eliska. “You know we’re to be married, don’t you?” he said to Zuba, as he pulled Eliska tightly to him. “My Papa paid half the dowry, already, and Bolda arranged it.”

“Oh Jacob, please don’t cause trouble. You are my intended, and we will marry.” Eliska said. “Zuba wasn’t flirting; I was nice because he helped us out. Nothing wrong with that, is there?”

“Just so he knows which way the crow flies. I’ll have nobody messing with my bride to be. I saw how he watched you when you turned your back! I won’t allow him to talk to you again! Do you hear me?”

“Talk to me? He hasn’t said a word! He won’t even look me in the eye!”

“You know what I mean!” Jacob jabbed his finger in Zuba’s chest, “and as for you, you big dumb donkey, just stay away or I’ll place a curse on you.”

Bolda came up and intervened. “Jacob, will you escort Eliska home? We’re stopping at grocers and be home later. Remember your manners!… Hanzi are you coming?”

“Well, I thought, I’d stay awhile, there’s this girl. What a girl, she keeps making eyes at me, smiling at me, dances every dance and slows down at the bandstand.” Hanzi drew a deep breath and continued, “I have to talk to her. Won’t take too long. I’ll be along quick. You’ll see, just say hello. Just hello, it won’t hurt, will it? No, it shouldn’t. OK, Papa? What you say, Papa? I won’t be long!”

“All right, all right! You wear me out. Just don’t get into any trouble.”

Zuba stood off to one side, fidgeting with his head down, and he muttered to Bolda, “Yu. ––Like. ––way I––play?”

“It was all right, I guess, just an audition, no pay.”

“I––play––again––with––you?”

“Ya, another time, in the summer. I’ll let you know.” Bolda dismissed him with a wave of his hand.

“I––play––tuu––ba-gud, don’t––I?”

“Yeah, sure, another time,” Bolda packed up his guitar and walked out. Zuba clutched his tuba case under his arm and with his head down, stumbled out of the dance house.

Jacob and Eliska picked up their instruments, and strolled arm and arm out the door, taking the wooded dirt path back to Litomysl. Ales Braun and his Freikorps gang followed behind. When Jacob and Eliska entered a tree covered part of the lane, the gang surrounded them.

“Hey gypsy boy, how about sharing the korunas they paid you tonight?” Ales snarled, hands on his hips, with his gang backing him.

“Just go away and leave us be.” Jacob clutched Eliska by the arm, and they continued walking.

“Why don’t we take it and share your girlfriend too?” Ales grabbed Jacob by the shoulder, twisted him around, and pulled back his fist, preparing to strike Jacob.

“No! Run Eliska!” Jacob cried, as he twisted loose and ran down the path.

“Wait, don’t leave me,” Eliska cried out, running after him.

They ran for several yards when a low hanging tree branch caught one of Eliska’s gold earrings, ripped the earring from her ear. She screamed, whirled and tumbled to the ground. She lay, petrified, her ear bleeding as the Freikorps surrounded her.

Jacob hesitated, and then ran away yelling, “I’ll get help!”

“Oh, such a pretty gypsy you are.” Ales held his hand out to her. “Here, let me help you up.”

Eliska hesitantly took his hand. With a quick jerk, Ales pulled her up and into his arms. “Now there, isn’t that better, sweet gypsy girl? You have nothing to worry on. Oooooh, your poor little ear, it’s bleeding.” He reached down and pulled Eliska’s skirt up to her ear, exposing her slender legs. “Let me dab it with your skirt.”

“Now, aren’t those lovely legs? They are as good as any German girl. Hey, boys, they say gypsy girls are put together differently than our girls. Let’s see!” Ales garlic breath was in Eliska’s face as he reached under her skirt, but before he went any further, Eliska kneed him in the groin.

“Oooo, you gypsy bitch!” moaned Ales, dropping to his knees, holding his groin with both hands. “Boys! Toss her around! Soften her up!”

The Freikorps grabbed her, one Freikorp on each arm, formed a circle and tossed her from one gang member to another.

“Toss her good!” Ales moaned as he stumbled to his feet.

Eliska flew around the gang, screaming. Frequently, a gang member stuck out his leg and tripped her to the ground. Each time she fell, they’d grab her by the arms, jerk her to her feet, and throw her around the circle again.

Meanwhile, still in the dance house, Hanzi was in earnest conversation with the girl who had caught his eye. Hearing his sister’s screams, he raced out of the dance house and saw that Eliska was in trouble.

He reached inside his vest to get his knife, but it was still on the floor of the dance house. Without hesitation, he raced to help his sister and leaped on the back of the biggest gang member.

Hanzi wrapped his arms around the man’s neck and held on for dear life. “Leave my sister alone, or you will be sorry, you’ll be sorry you messed with my family. I got you now, do you give up? You messed with the wrong guy I tell you. Give up, I say!”

“Eldric! Hartmut! Kill the little bastard; then we’ll have a go at his sister.” Ales moaned, still holding his groin.

The two gang members pulled Hanzi off and threw him to the ground and kicked him violently.

A large man stood by the outskirts of the group, he hesitated and then stepped in the circle. “Doon––do,” Zuba stammered. “Leave––be!” He paused again. They no stop. What do now? ––Maybe bulldog. ––No want hurt––Maybe separate them like two hogs fighting.

Eliska screamed, “Please don’t hurt Hanzi, please!” Her screams awoke a fierce fury within Zuba’s heart. A wave of anger swept over him as he cried out “No More!” He stepped behind Eldric and Hartmut grabbed Eldric’s collar in one hand and Hartmut’s collar in the other hand, and with a quick tug, he pulled both backward. Off balance, they flew behind Zuba, rolling butt over teakettle, on the ground.

“Get the stupid fool! Kick him good!” Ales yelled and charged Zuba. He head-butted Zuba in the stomach, but Zuba didn’t flinch. With one mighty push to the back of Ales’s head, Zuba sent the gang leader, face down, to the ground. Zuba turned and wrapped his arms around two more gang members, a headlock with one arm over each of their necks and squeezed. “No––more––hurt!” He let go of the bulldogged gang members. They gagged and bent over holding their throats. He grabbed them by the seat of the pants and shoved them into the rest of the gang, collapsing the whole bunch into a pile of squirming arms and legs. Hanzi, not to be outdone, jumped into the fray and delivered a few well-placed kicks.

The Freikorps gang hesitated, sensing they were in over their heads, they picked up Ales and ran off.

Hanzi strutted, spit and yelled after them. “Run, you cursed Germans. I told you not to mess with me! May the crows peck out your eyes and the dog’s pee on your beds!”

“Are you all right? I showed them didn’t I Eliska?” Hanzi helped his dazed sister up.

“My back hurts, and I twisted my leg,” Eliska replied shakily

Zuba picked up Hanzi’s headpiece and handed it to him.

“Zuba, where, how?” Eliska said.

“Oh, he helped a little, holding my scarf, so it doesn’t get dirty. You know how wild I get when I get mad.” Hanzi strutted, swinging at imaginary foes.

“I think he helped more than that, dear brother.” Eliska brushed herself off. “Thank you, Zuba.”

Zuba hung his head and stared at his shoelaces. He tried to speak, but only a slight croak came out.

“Sounds like you swallowed a frog in the fight,” Hanzi teased. “Zuba is a zaba, a frog.”

“Now be kind Hanzi, he helped us twice tonight. He is a velky tichy zaba (big silent frog),” Eliska said, a teasing glint flickered in her eyes. She put one hand on Zuba’s arm and placed her other hand, in his work calloused right hand. “Will it hurt your feelings if I call you big silent frog?”

Zuba stood silently, heart pounding, longing to look at her, to talk to her, but his eyes pondered the pebbles on the ground. Lavender splash water smells good––He dropped her hand and reached to take her other hand off his arm. Shouldn’t touch me. ––I should be hurt. ––Call me a big silent frog. ––that kinda nice, ––I like––Wish I could tell her.

As Zuba’s hand rested on Eliska, Bolda, Jacob and a group of Roma men, ran up.

“Take your filthy hands of my daughter, you fool!” Bolda lashed out with his walking stick hitting Zuba’s arm.

“Are you hurt, my love?” Jacob said, rushing to Eliska’s side.

Eliska pleaded with her father, “Stop Papa! Zuba helped us. If it weren’t for him, I’m afraid of what could have happened.” She glared at Jacob. “Where were you, my husband to be? Where were you when I needed you? When the Germans jumped us?”

“Oh, the best thing to do was to get help; see how well it worked out?” Jacob unashamedly denied his cowardice.

“I whipped them, Papa! I got mad! Bang! Boom! Bam! I lowered the boom,” Hanzi proclaimed.

“Yes Hanzi, I bet you did. Now, take your sister home, have Mama treat her ear,” Bolda said.

Eliska, clung to Hanzi’s arm with one hand while holding her side with the other. She limped along beside him on their way home. Jacob hurried to catch up, and when he did, he reached out his hand to Eliska, and she slapped it away. “See how well that works out,” Eliska snapped.

Bolda faced Zuba and stamped his walking stick hard on the ground, “It’s best you not come around Eliska no more. I’m grateful for your help but we Roma can handle it. There wouldn’t be trouble if I hadn’t let you play in the band. Understand? Roma and Gadje don’t mix.”

Zuba hung his head, nodded and turned away before Bolda could notice the tears in his eyes. Done it again. ––Always mess up. ––Why can’t I stay with my people even though they make fun of me? I deserve it. ––I am so dumb! ~~~~~~

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Don Pawlitschek is a dyed-in-the-wool, promoter, and entrepreneur. • Over 2000 auctions, appraisals, real estate sales, consulting assignments, and funding projects completed nationwide since 1980! • Minnesota Licensed Auctioneer • Bonded Western Surety bond • Certified Auctioneer CA • Certified Personal Property Appraiser Instructor-CPPAI • Certified Personal Property Appraiser-CPPA • Certified Real Estate Auctioneer-CREA • Certified Management and Fund-Raising Auctioneer-CCFRA • Certified Online Internet Auctioneer-COI • 30 yrs., a Real Estate Agent, Broker, and Investor Agent, • Designed a plastic hog flooring slat with strength enough to span eight feet, ventilate and flush manure. He was issued Patent No. 4,135,339 on Jan 23rd, 1979. • Listed in Who’s Who since 1985. • Recorded eleven albums; He wrote, directed, and acted in a TV pilot called “Crime Does Not Pay.” Made for the family audience, it featured his family, places of interest from the Upper Midwest, acts he had on his shows, their act, and other features. • Has written eighty stories, poems and comedy routines • Released his first full-length novel. He sometimes writes under the pen name of Popps Dundee. • Photographer, producing an annual family album and has shot the candid shots at several weddings. • Owns a small recording studio and has performed and recorded several albums of country and 50s music. • In 1992, as a concert promoter, he formed the company Butterfly Stew and promoted shows at various Civic Centers, such as St Cloud, Sioux City, Sioux Falls, Lacrosse WI. • He had a full range of acts, heavy into country music. From Nashville, he had Connie Smith, Jean Shepard, Bobby Rice, and Jack Greene (1967 male vocalist of the year). From Hollywood, he had Donna Douglas (Ellie Mae of the Beverly Hillbillies). • Performs benefit auctions, is a public speaker, and performs in and directs the musical group Sugarloom, appearing before thousands of people since 2016. He also performs as a solo artist. • He has five children and nineteen grandchildren, each one his favorite. He was married to the same woman since 1965. Thank God, she was kind enough to put up with his comings and goings.